Although there are so many triadic formulas in the New Testament, there is not a word anywhere in the New Testament about the ‘unity’ of these three highly different entities, a unity on the same divine level. … In Judaism, indeed throughout the New Testament, while there is belief in God the Father, in Jesus the Son and in God’s Holy Spirit, there is no doctrine of one God in three persons (modes of being), no doctrine of a ‘triune God,’ a ‘Trinity.’

But how does the New Testament understand the relationship between Father, Son, and Spirit?

But how does the New Testament understand the relationship between Father, Son, and Spirit?There is probably no better story in the New Testament to show us the relationship of Father, Son and Spirit than that of the speech made by the protomartyr Stephen in his own defense, which has been handed down to us by Luke in his Acts of the Apostles. During this speech Stephen has a vision: ‘ But he, full of the Holy Spirit, gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God; and he said, ” behold, I see the heavens opened and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God.”‘ [Acts 7:55-56] So here we have God, Jesus the Son of Man, and the Holy Spirit.

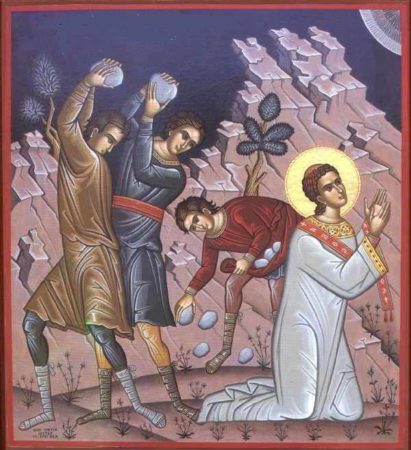

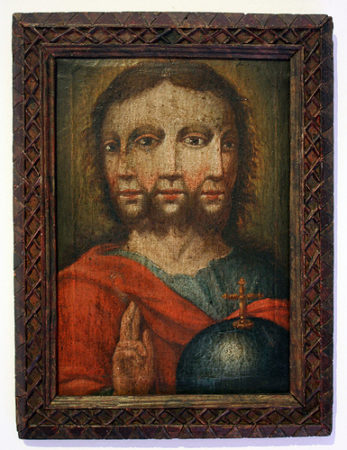

But Stephen does not see, say, a God with three faces, far less three men in the same form, nor any triangular symbol of the kind that was to be used centuries later in western Christian art. Rather:

But Stephen does not see, say, a God with three faces, far less three men in the same form, nor any triangular symbol of the kind that was to be used centuries later in western Christian art. Rather:– the Holy Spirit is at Stephen’s side, is in Stephen himself. The Spirit, the invisible power and might issuing from God, fills him fully and thus opens his eyes: ‘ in the Spirit’ heaven opens to him.

– God himself (he theos = the God) remains hidden, is not in human form; only his ‘glory’ (Hebrew kabod, Greek doxa) is visible: God’s splendour and power, the brilliance of light which issues fully from him.

– Finally Jesus, visible as the Son of Man, stands (and we already know the significance of this formula) ‘at the right hand of God’: that means in throne communion with God, in the same power and glory. Exalted as son of God and taken up into God’s eternal life, he is God’s representative for us and at the same time, as a human being, the human representative before God.

… According to the New Testament the key question in the doctrine of the Trinity [i.e. the aforementioned triad] is not the question which is declared an impenetrable ‘mystery’… How three such different entities can be ontologically one, but the christological question how the relationship of Jesus (and consequently also of the Spirit) to God is to be expressed. Here the belief in the one God which Christianity has in common with Judaism and Islam may not be put in question for a moment. There is no other God than God! But what is decisive for the dialogue with Jews and Christians in particular is the insight that according to the New Testament the principle of unity is clearly not the one divine ‘nature’ (physis) common to several entities, as people were to think after the neo-Nicene theology of the fourth century. For the New Testament, as for the Hebrew Bible, the principle of unity is clearly the one God (ho theos: the God = the Father), from whom are all things and to whom are all things.

So according to the New Testament, Father, Son and Spirit are not metaphysical and ontological statements about God in himself and his innermost nature, about a static being of the triune God resting in himself and not at all open to us. Rather, these are soteriological and christological statements about how God reveals himself through Jesus Christ in this world; about God’s dynamic and universal activity in history, his relationship to human beings and their relationship to him. So for all the difference in ‘roles’ there is a unity of Father, Son and Spirit, namely as an event of revelation and a unity of revelation: God himself is revealed through Jesus Christ in the Spirit. This is a thought-structure shaped in the framework of the Jewish-Christian paradigm which, as a structure – unlike that of a ‘triune God’ – need not have been absolutely alien to a Jew even down to the present day..

pgs 95-97

Hans Küng’s paragraph is a clever half-truth that trades on a false dilemma. Yes, the New Testament does not hand us fourth-century technical terms like “homoousios,” and yes, it shows the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in differentiated relation. But from that it does not follow that the apostles knew only a “soteriological triad” and no unity of being. The apostolic writings repeatedly attribute to the Son and the Spirit what Israel’s Scriptures reserve for the one LORD alone—creation, sovereignty, the divine Name, the right to receive worship, the prerogative to forgive sins, the sending of the Spirit, and the presence of the Glory—and they do so while refusing every hint of polytheism or modal masquerade. That is not a later Nicene invention; it is the raw grammar of the New Testament itself.

ReplyDeleteKüng’s showcase text, Stephen’s vision in Acts 7, does the opposite of what he wants from it. Stephen, “full of the Holy Spirit,” gazes into heaven and sees “the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God” (Acts 7:55–56). This is not a picture of one true God and a promoted creature. In Jewish categories, to stand at the right hand is to share in the divine kingship; that is why the New Testament so often frames Jesus with Psalm 110:1 and Daniel 7. The “Son of Man” of Daniel is not a mere envoy; he receives dominion, glory, and a kingdom, and in the Greek tradition of Daniel he receives the service due to God. When Revelation shows the heavenly liturgy, it is not a tale of two thrones and two kinds of honor; there is one throne and a single doxology “to him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb” (Rev 5:13–14). If heaven is the measure of orthodoxy, the “co-enthronement” of the Son is precisely the unity Küng denies.

The attempt to quarantine New Testament triads as “mere roles” collapses as soon as one asks why the Son and the Spirit keep doing what only God can do. John opens by calling the Word what God is and then excluding him from the class of creatures: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… all things came to be through him, and without him not one thing came to be” (John 1:1–3). Paul “re-monotheizes” the Shema by placing the Son inside it: “for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist” (1 Cor 8:6). The point is not two deities sharing tasks; it is one divine identity expressed as “from” and “through,” the distinguishing marks of Father and Son in the single work of creation and redemption. Hebrews calls the Son “the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his hypostasis,” the one who “upholds all things by the word of his power,” and then addresses him without flinching as God whose throne is eternal (Heb 1:3, 8–12). Colossians says that in him “all the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily” (Col 2:9). John has Thomas confess the risen Jesus, face to face, as “my Lord and my God” (John 20:28), and neither evangelist nor Christ slaps his wrist for blasphemy. If these are not “ontological” claims, the word has no meaning.

Nor can the Spirit be reduced to an impersonal “power.” The Spirit speaks, sends, searches, wills, intercedes, and can be lied to and grieved (Acts 13:2; 1 Cor 2:10–11; 12:11; Rom 8:26–27; Acts 5:3–4; Eph 4:30). Peter’s verdict is not poetry: to lie to the Holy Spirit is to lie to God (Acts 5:3–4). Jesus promises “another Paraclete” and then names him the “Spirit of truth” who proceeds from the Father and takes from what is the Son’s (John 14:16–17, 26; 15:26; 16:14–15). That is personal, relational language embedded in the divine life, not a human metaphor for a gust of force.

DeleteKüng insists there is “no doctrine of a triune God” in the New Testament because the words “one essence, three persons” are not on a page. But Catholics (and the Fathers before Nicaea) have never claimed the Bible contains a ready-made scholastic formula; they claim it contains the realities that demand that formula. The realities are everywhere: baptism “into the name” (singular) “of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt 28:19); the apostolic blessing that invokes grace, love, and communion from the three together (2 Cor 13:14); the one salvific action distributed without division among Spirit, Lord, and God (1 Cor 12:4–6; Eph 4:4–6; 1 Pet 1:2). If “unity” is to mean anything in this canon, it is the unity of the one God whose single operations ad extra reveal distinct personal origins ad intra. That is precisely why the Church later reached for “ousia” and “hypostasis”: to name, without confusion or division, what Scripture forces upon us—the Father is God, the Son is God, the Spirit is God; the Father is not the Son or the Spirit; yet “the LORD our God, the LORD is one.”

Reducing all this to “soteriological statements” is a rhetorical maneuver that fails on its own terms. Salvation in Scripture is not a bare event with no revelation of God’s being; it is God giving himself. When the Word becomes flesh (John 1:14), when the Father sends the Son in love (John 3:16–17), when the Spirit pours the love of God into our hearts (Rom 5:5), the economy is the immanent life opened to us. Jesus speaks of the glory he had “with” the Father before the world existed (John 17:5) and of the Father’s love for him “before the foundation of the world” (John 17:24). He tells us the Spirit “proceeds” from the Father (John 15:26). These are not mere job descriptions; they are windows on eternal relations. The fourth-century terms gave the Church stable grammar to protect exactly that.

The appeal to “ho theos” as if the article settled everything proves far too much and contradicts John himself. The New Testament can reserve “the God” as a way of denoting the Father without denying the Son’s full deity, just as it can call the Father “greater” in the economy without demoting the Son’s nature (John 14:28). John balances “the Word was with God” with “the Word was God,” and the evangelist’s habit of qualitative predication in no way licenses a creaturely Christ. Paul’s “one God… and one Lord” is not a demotion of the Lord; it is the Christian confession of Israel’s one God split open along the lines of Father and Son while remaining one. If this feels alien to a flat, unitarian monotheism, that is because the Bible never taught a flat, unitarian monotheism.

DeleteFinally, Küng’s “no doctrine of the Trinity in the New Testament” functions for Jehovah’s Witnesses as a permission slip to ignore what the apostles actually do with Jesus. They pray to him, invoke his name in salvation, worship him in heaven’s liturgy, place him on the Creator side of the Creator/creature line, and identify him with the LORD of Israel’s Scriptures—all while preaching one God. Nicaea did not conjure that out of thin air; it fenced it against a novelty that could not bear the scandal of the Son’s equality. If you refuse the Church’s clarifying words, at least be honest about the apostolic facts: the Father is not the solitary God “over against” the Son; the Son is not a glittering servant merely “at God’s right hand” as a token of favor; and the Spirit is not God’s breathless energy. The New Testament compels us to say more, and the faith of the Church—before and after the fourth century—does exactly that.